On Density

Thursday, February 19, 2009 at 08:57PM

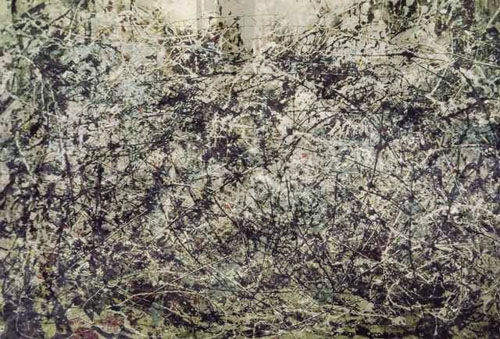

Thursday, February 19, 2009 at 08:57PM Below are five images. The first is a photograph of snow on bushes in my backyard. As you page down to view the successive images, you will see a pattern emerge through the snow covered bushes. I will identify this pattern after it fully appears in the fifth image.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

The final image is Jackson Pollock's painting called Number One-1948. Pollock is famous for pouring paint onto canvases placed on the floor. His art has far more method to it than people think, but I am not concerned with his methods. The results are images with a uniquely dense quality to them. The fullness of the densities Pollock arrived at in Number One are hard to see in the small image here, but the overall quality is evident and characteristic of the paintings for which Pollock is most well known. I merged Pollock's painting with the photograph of snowy bushes as a means of revealing the aesthetic densities that are part of our everyday surroundings. The bushes and Pollock's painting share a similar density, revealed in part by the Photoshop trick I employed of layering the snow image over the Pollock image and successively reducing the opacity of the top layer. I think that visual density has a strong aesthetic appeal. I will fill out this thought in subsequent posts.