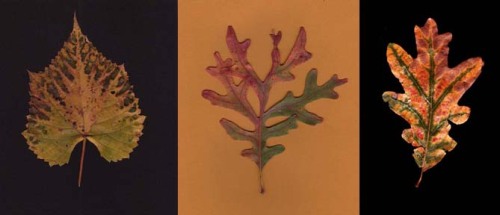

Leaf Compositions

Thursday, February 5, 2009 at 06:04PM

Thursday, February 5, 2009 at 06:04PM Toward the end of his life, Henri Matisse created shapes by cutting them out from colored papers. His works of this period are called "cut-outs." Matisse could array a set of simple shapes, such as in “La Gerbe”, to produce a delightful composition. Today, we have Photoshop. I scan leaves and play with Photoshop's layers and difference filter.

Leaf Mash Up

For “Leaf Mash Up”, I started with a “J” form of White Oak leaf, made copies on several layers, and obtained the multicolored effect with the difference filter. The interesting thing about the difference filter is that you are not sure what will come out when you use it, and the surprise can bring delight.

Curved Red

“Curved Red” employs a Red Oak leaf, which I copied twice and rotated each copy. Again, the Difference filter is responsible for the coloring.

Ginkgo

I liked the colors that came out in “Ginkgo”. Here there are only two layers, the base and its copy, rotated 90 degrees clockwise.

Maples

“Maples” uses red and Japanese maple leaves, superimposed.

Pin Oak Study

For “Pin Oak Study”, I rotated a pin oak leaf eight times. The difference filter creates the “interference” effect, somewhat as in the crests and troughs of colliding waves.

Swirl

“Swirl” is a red oak leaf rotated and superimposed on itself, with a gradient background.